Poetry By Any Name

- Erin Conway

- Feb 16

- 3 min read

I knew where my first name came from. Erin I liked.

“We named you Erin. Liked it when I heard it on the Waltons. But, if we hadn’t named you Erin, we were either going to choose Rachel or Hannah,” my dad had explained more than once.

Since we had a family friend with a daughter named Rachel, I had never considered that name. It didn’t feel mine, but somehow Hannah struck me differently. I could have been a Hannah.

I knew where my middle name came from. Frances I didn’t.

“A great aunt of your mother’s.” That was all my dad could remember.

Years ago, my brother asked if I had considered having a Hebrew name.

I looked it up. “Your Hebrew name is your spiritual call sign, embodying your unique character traits and G‑d-given gifts.”

Immediately Hannah came to mind. I dug a little deeper about what the name meant.

Hannah means ‘favor or grace’. She is depicted as a womanless child. Hmmm.

I searched for famous Hannahs and discovered Hannah Arendt. I didn’t read extensively about her. The fact that she was a poet and someone who was considered thought-provoking was enough to confirm an affinity. It was the perfect intersection of the history of my naming, Jewish identity and historical reference points. I told myself that would be my Hebrew name, at least unofficially.

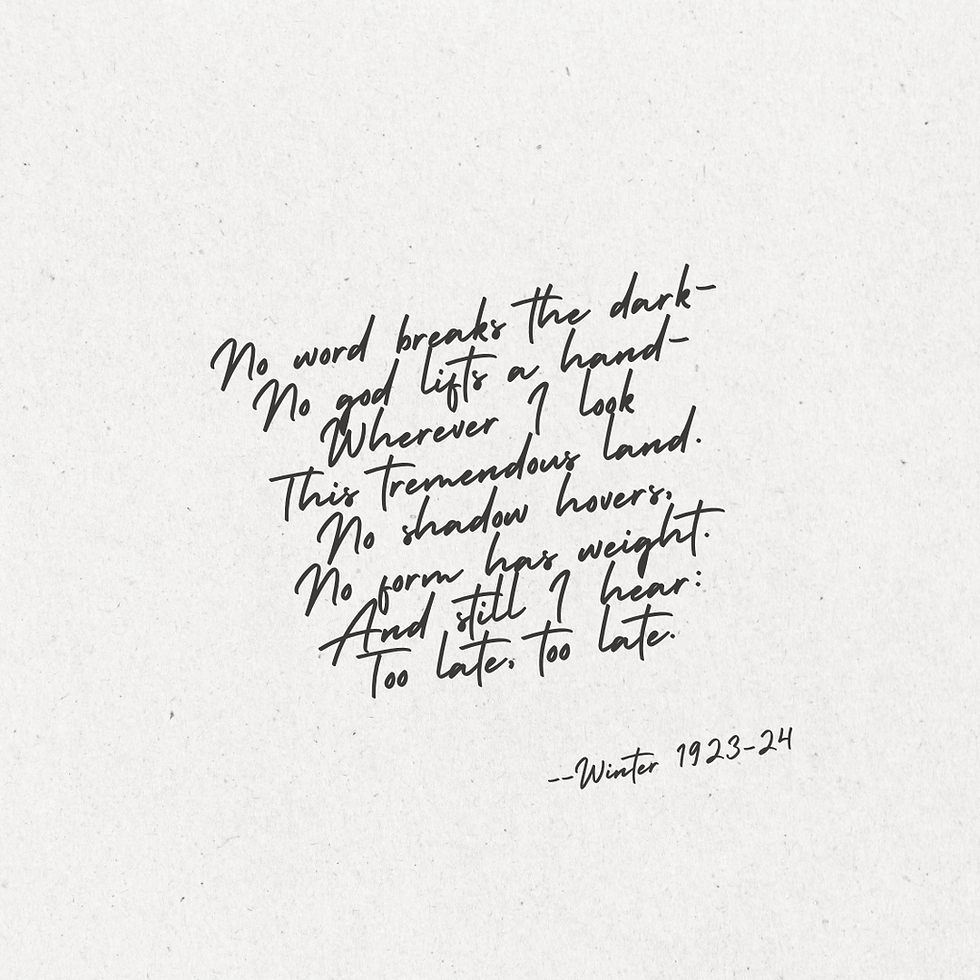

A new book of Hannah Arendt’s compiled poetry was published this year, “What Remains: The Collected Poems of Hannah Arendt”. In the text, the opening chapter was a reflection. I was enthralled, not the poetry content, but the way she understood and used poetry.

Arendt considered notebooks to be ‘thinking exercises’. “She used the page as one might use a stage, arranging voices to place herself in conversation with others.” (xxvi). I smirked. Sometimes my words did not even make it into a notebook. They were swooping phrases on napkins and ripped open envelopes. I preferred them as phrases, snippets, multiple thoughts in pieces. Maybe I would put them together and maybe not. Their value was in their immediate outpouring and sudden evaporation that sunk back into me as I read them.

“Arendt wrote poems to record events, reflect on experiences, and engage in what she called the ‘free play of thinking’.” (xv) “. . .poetry is the form closest to thinking itself.” (xxi) “Arendt wrote poems because she had found in them a language that allowed her to weave together thinking and experience. . . The language of poetry was a way of thinking for Arendt; it was what she called, ‘poetic thinking.’” (xxi).

“Poetry,” she argued, “whose material is language, is perhaps the most human and least worldly of the arts, the one in which the end product remains closest to the thought that inspired it.” (xxiii)

Free Play of Thinking. Poetic Thinking. Like the idea of Hannah as a Hebrew name, I didn’t understand these words, I felt them deep in my stomach. Each name for poetry spread, no radiated, upwards into my chest.

“Your Hebrew name functions as a conduit, channeling spiritual energy from G‑d into your soul and your body.”

What remains? Not poetry by any name, but by the name I chose.

"What Remains: The Collected Poems of Hannah Arendt” (2025) translated and edited by Samantha Rose Hill with Genese Grill. Liveright: New York.

Recent Posts

See AllI have reflected on Passover. Not every year, but most years, a musing surfaces. It is the only Jewish holiday that I experienced first...

Light cannot be ‘new’. It’s different. A different light. Stories are never new. They’re told differently, heard differently when...

In her book, "My Jewish Year," Pegrebin adds Shabbat as a chapter inside the trajectory of the other holidays of the year. Is this...

Comments